As a former teacher and current member of the eSpark team, I’m intrigued by all things education. Teaching preschool is especially fascinating as it’s full of misconceptions—even more so than the teaching profession itself. Many people incorrectly assume that preschool students are incapable of learning math, reading, and abstract thinking at such an early age. In actuality, early learners are more than capable of learning these skills if lessons are purposeful and connected to child’s play.

Another misconception is one I am embarrassed to say I was guilty of myself. As a high school teacher, I had a limited understanding of what early childhood educators need to do or know in order to teach preschool.

Over the years, it’s become abundantly clear to me that preschool teachers have one of the most challenging roles. Early childhood educators must both master childhood development and be able teach engaging math and literacy lessons within a short, unpredictable class day. Teaching students during some of the most crucial years, preschool teachers have an enormous responsibility—and a really tough job.

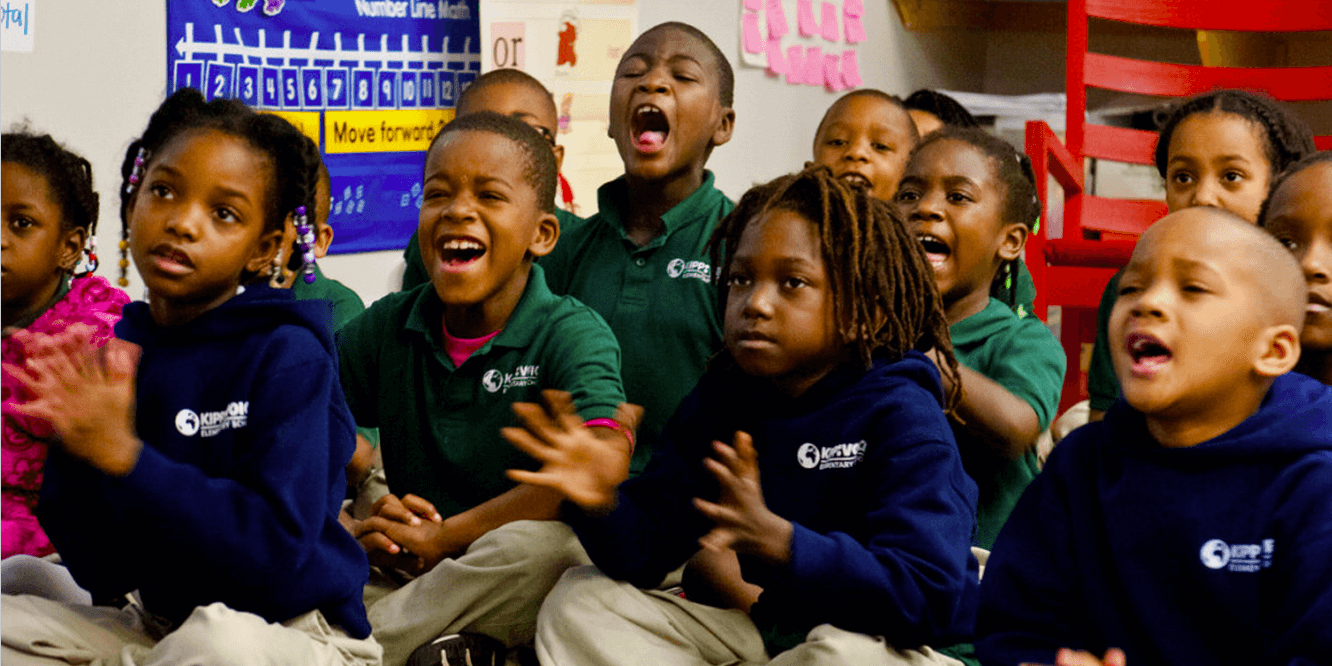

But, as the the NAEYC highlights, high-quality teaching at this age is of the utmost importance: “On starting kindergarten, children in the lowest socioeconomic group have average cognitive scores that are 60 percent below those of the most affluent group… Moreover, due to deep-seated equity issues present in communities and schools, such early achievement gaps tend to increase rather than diminish over time.” If low income students are to have any chance of keeping up with their peers, they must receive targeted support and intervention at an early age. Tasked with narrowing a widening achievement gap, early childhood educators need all of the resources they can get.

How can we nurture a love of learning?

How can we best teach preschool so that every student can receive developmentally appropriate early childhood education? First, we need to understand teaching preschool is not just about play or math and literacy content; it is about facilitating a starting point, a love and understanding of learning. Herbert Ginsburg, who teaches a course at Teachers College for early childhood education students called The Development of Mathematical Thinking, says, “preschools (are) caught between a “false dichotomy” of structure, assessment-oriented lesson plans and free play.” Rather than embracing a dichotomy of play and education, a successful preschool lesson is one that inspires students with the potential of learning and uses play to teach young learners math or literacy content.

Preparing students for state standards does not mean that students shouldn’t also be collaborating, playing outside, making art and learning to deal with their emotions and socialize. Karen Nameth, director of the NAEYC says, “Nothing in the standards forces us to teach preschoolers as if they were older students.” Exploratory, hands-on and creative play is what allows children to build a strong foundation to later have success and demonstrate mastery of standards. For young children, play is the most developmentally appropriate method of instruction, and if students are not taught in a developmentally appropriate way, it’s unlikely that they will develop a love of learning.

So how we move past this false dichotomy? The answer lies in being purposeful about our respect for the learner and the teacher.

What does a successful preschool teacher look like?

Preschool students are capable of far more than we think they are. Even at age three, children understand the concepts of subtraction.They understand that if you take away food from their plate, they have less food than they started with. Preschool students are capable of abstract thought; they can count using their fingers as representations for other objects and predict what an imaginary character will do next.

As children develop, they follow well-documented sequences. By using playful games to introduce preschool students to counting or writing letters, teachers give students the foundation to understand numerals and to begin to communicate with the written word.

Teaching preschool, just like all strong teaching, starts with master teacher facilitators because, paradoxically, teaching our youngest learners means knowing more, not less. As the NAEYC states, “the most powerful influences on whether and what children learn occur in the teacher’s interactions with them, in the real-time decisions the teachers makes.” Successful preschool educators understand that the role of the teacher is central to facilitating social, emotional and cognitive growth- and to meaningfully implementing platforms that can spark deeper learning. Historically, public education has underestimated the importance of preschool teachers and the ability of early learners. Preschool teachers must have a clear understanding of child development so they can support students in learning to self regulate, focus attention, reflect, collaborate, acquire language, think abstractly and to understand sequences in literacy and math. If we are to tackle the achievement gap early on, we must first recognize the challenge and importance of early education.

Preschool teachers can make small, purposeful changes to reconcile the false dichotomy of free play and content-driven teaching. Instructional changes as simple as providing specific feedback and acknowledging student creations can be transformative. Preschool teachers can use affirmation as sites of metacognition, praising students with prompts such as “Great, you did that because….” or “Great job. Why did you do that?”

Preschool educators should also take pains to teach self-regulation. Self-regulation is invaluable to children facing difficult circumstances because it will help them to self soothe, problem solve, focus attention and learn metacognition. To teach self-regulation skills, a teacher can simply make space for a child’s agency through extending conversations and reflections about a block tower he or she created. Interviewing students about their play, asking them to reflect, to problem solve and to answer “why” are all important skills preschool students are capable of.

How can we find the time to challenge and support all students?

Where can teachers find the time for these types of conversations? The answers can be found in blended learning. The American Academy of Pediatrics gives us recommendations on this use of blended learning, highlighting the benefits of active, rather than passive media use. Students who are active media users use a touchscreen, receive feedback, and must engage with or react to digital content.

So, instead of thinking about blended learning as passive for students and as a “replacement” or “teacher proofing” tool for teachers, I now think about how blending allows a teacher’s role to be elevated to that of facilitator. When teaching preschool means blending learning, we are actually creating the time that teachers don’t have. When students are engaged in individualized material, teachers have the time to form those personal relationships and offer the feedback that deepens and extends play.

When looking at interactive media use in the early childhood classroom, The Fred Rogers Center offers various “active ingredients” that promote engagement such as “characters who children build relationships with, elements that promote guided play and avoidance of distractions.” So, in thinking about blending learning, certain foundations must be in place. Content must be personalized for students. Students need scaffolding just above their current mastery level. Carefully chosen, individualized content can help ensure that students are introduced to the sequences of math and literacy concepts they need.

This type of interactive technology use can give students new avenues through which to communicate ideas, feelings, investigate the environment, record a story, create a picture and document and revisit their work. Classroom technology will allow students to express themselves and to get practice in the four domains of language and literacy, and will allow teachers to create on-going portfolios to document a child’s progress.

The Fred Rogers Centers also recommends that student screen time is active and limited to only about 15-30 minutes of focused attention to ensure students are engaged. Young children are still learning to focus and self-regulate, so short, purposeful use of interactive media can bring a creative advantage to children.

What can we learn from preschool teachers?

As a former middle school and high school teacher, I wish I spent more time learning from the men and women who teach preschool, who use play as a starting point to deepen content. This type of awareness across grade bands, specifically in grades PreK-3, would mean more student-centered teaching for all of our learners.

If teaching preschool means integrating blended learning to support student voices and developmentally necessary math and literacy content, the benefits of early childhood education can be an even more impactful force for educational equity. We just need to look to the success we’ve seen with programs like Head Start, the Race to the Top-Early Learning Challenge, and from states like New Jersey that have created comprehensive preschool standards.

Looking for new forms of classroom management for your preschool students? Try eSpark for free today for personalized, data-driven learning.