Early childhood learning is perhaps the most critically important stage in a person’s cognitive and emotional development. Patterns and behaviors emerge that set in motion how that person will continue to learn as they age. Of course, each child is different, and for every rule there are exceptions—but one need look no further than the tremendous and largely deleterious effect the COVID-19 pandemic has had on young kids’ educational growth. The impact has reinforced that a child’s early learning years are vital to development, and how a society values education is reflected in what degree it makes it obtainable.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, an intergovernmental group of 38 countries created to stimulate economic growth, developed a report for the G20 Education Working Group in which it stated that up through age 6 in particular, a child’s brain has an “extraordinary capacity for learning.” By this age, the brain has reached 90% of its adult volume. In the first several years of life, the brain can develop as many as 1 million new neural connections every second. Moreover, early childhood is the time when a person’s brain is at its most malleable to change based on experience. If you’ve ever heard someone’s ability to learn new things described as being like a sponge soaking up water, the aptness of that metaphor can be traced to early childhood learning.

A 2016 Rand Europe study concluded that investment in early education yields a better return on investment than if the same amount were spent on education later in life. Early education contributes to social and emotional well-being and lessens the risk that a child will drop out of school or repeat a grade. Giving children the chance of a strong start in their educational life reduces the costs of addressing learning and other developmental problems later on because those problems tend to grow as a child continues through schooling. Early childhood education opportunities can also allow mothers to work, breaking cycles of poverty.

In a 2012 report, the OECD found the United States ranked 28th in the percentage of 4-year-olds enrolled in early education. Ten years on, the question is: How does the U.S. measure up now? eSpark examined government education data compiled by the OECD to see how early childhood education differs across the world.

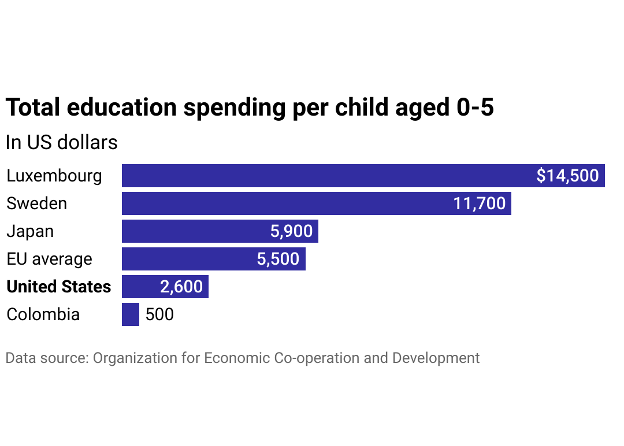

Early education spending per child

On average, countries that belong to the OECD spend 0.7% of their GDP on early childhood education and care, though amounts vary widely among countries. In many other nations—notably Sweden, Norway, and Denmark—early childhood education is heavily subsidized. But not so in the U.S.—a New York Times report that referenced OECD data showed that while Norway spends nearly $30,000 on average per child, the U.S. spends a paltry $500 on child care. Much of that is geared towards families below the poverty line, to say nothing of those hovering just above it whose struggles are comparable.

In Sweden, nearly half of 1-year-olds, 91% of 2-year-olds, and 97% of 5-year-olds are enrolled in an early childhood education program. (This is in part a reflection of a high rate of dual-income households, where both parents work full-time.) Participation rates for 3-year-olds in Japan was 81%. Colombia has increased government spending on preschools for low-income families but found that intensive training of teachers was necessary for significant improvements among students.

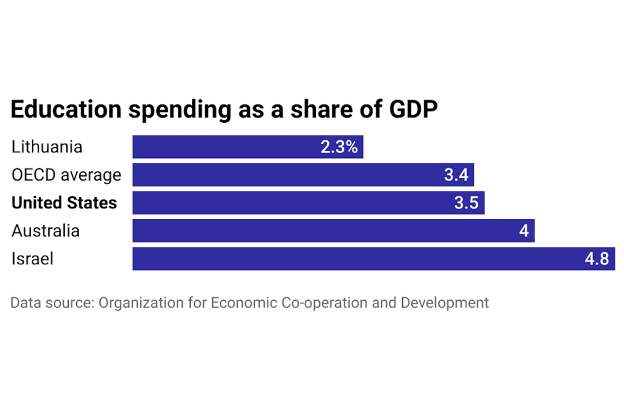

Total education spending as a percentage of GDP

The U.S. spent $14,400 per full-time equivalent student at an elementary and secondary school in 2018—higher than the average $10,800 spent by other OECD nations. At the postsecondary level, that amount rose to $35,100. That’s nearly double the $17,600 average of OECD countries. Still, as a percentage of gross domestic product, the U.S. barely strains past dead center, despite being one of the largest and wealthiest nations in the world. Moreover, its FTE spending rose just 3% between 2010 and 2018, whereas countries such as Germany, Sweden, Iceland, Israel, and the Czech Republic all reported double-digit growth in education spending. Even Chile rocketed spending by more than 50%.

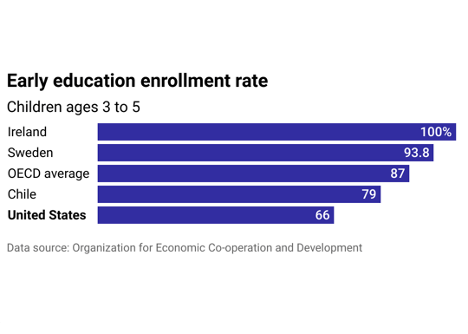

Early education enrollment rates

Children in Ireland can begin early childhood education when they are 2 years and 8 months old and continue until they transfer to a primary school. Preschools are free. In Sweden, 1-year-olds are entitled to a place in an early childhood education or care program. Chile expanded access to early childhood education significantly in 2015, resulting in better abilities in math, reading, and social sciences in advance of kindergarten.

In its 2021 State of Preschool Report, the National Institute for Early Education Research found that in all but six states preschool enrollment decreased and in seven states it fell by more than 30%. Concurrently, funding decreased in 20 states due to the pandemic, and five states—Indiana, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho—lacked a preschool funding mechanism altogether. While support is strong among the voting public for national universal pre-K, government subsidies such as those from the 2020 CARES Act remain a crutch, rather than a long-term sustainable solution. Four states presently have universal preschool—Florida, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

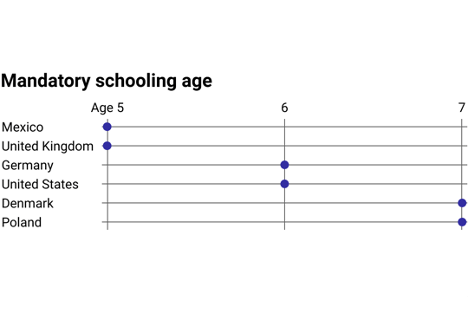

Mandatory schooling age

The best age to “require” a child to start school is still in debate. A Stanford University study found that children who did not enroll in kindergarten until they were age 6, instead of 5, showed reduced signs of inattention and hyperactivity when they reached 7 and then 11, the two age markers identified by study results. In the United States, the age at which children begin school varies by state, from a calendar-conditional 5 up to as old as 8 in Pennsylvania and Washington state.

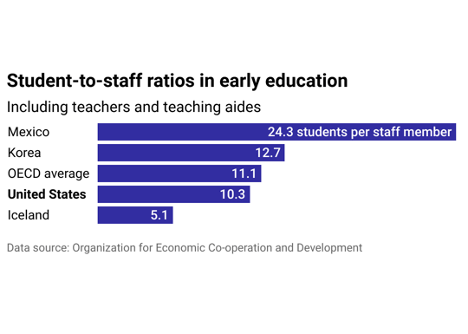

Average child-to-staff ratios

Teacher-student, or more collectively child-staff, ratios are often considered a key measure of how effective early childhood programs can be. The National Association for the Education of Young Children recommends ranges from 4-to-1 for infant care to 15-to-1 for K-3 education. The association also recommends not more than eight children to a class in the case of infants and not more than 30 in an early elementary school class.

The variance in child-staff ratios depends on a number of factors, including the number of direct care children in a specific age range require, the degree of educational components involved in their care, and what daily activities are involved. Mexico, with a child-staff ratio more than twice that of the U.S., has made preschool obligatory for children as young as 3. Iceland has one of the highest enrollments in early childhood education and care, and also provides more educators and support staff per enrolled child than the U.S.